Python 线程与协程

选自: PyTips 0x12 & 0x13

线程

要说到线程(Thread)与协程(Coroutine)似乎总是需要从并行(Parallelism)与并发(Concurrency)谈起,关于并行与并发的问题, Rob Pike 用 Golang 小地鼠烧书的例子 给出了非常生动形象的说明。简单来说并行就是我们现实世界运行的样子,每个人都是独立的执行单元,各自完成自己的任务,这对应着计算机中的分布式(多台计算机)或多核(多个CPU)运作模式;而对于并发,我看到最生动的解释来自 Quora 上 Jan Christian Meyer 回答的这张图 :

并发对应计算机中充分利用单核(一个CPU)实现(看起来)多个任务同时执行。我们在这里将要讨论的 Python 中的线程与协程仅是基于单核的并发实现,随便去网上搜一搜(Thread vs Coroutine)可以找到一大批关于它们性能的争论、benchmark,这次话题的目的不在于讨论谁好谁坏,套用一句非常套路的话来说,抛开应用场景争好坏都是耍流氓。当然在硬件支持的条件下(多核)也可以利用线程和协程实现并行计算,而且 Python 2.6 之后新增了标准库 multiprocessing ( PEP 371 )突破了 GIL 的限制可以充分利用多核,但由于协程是基于单个线程的,因此多进程的并行对它们来说情况是类似的,因此这里只讨论单核并发的实现。

要了解线程以及协程的原理和由来可以查看参考链接中的前两篇文章。Python 3.5 中关于线程的标准库是 threading ,之前在 2.x 版本中的 thread 在 3.x 之后更名为 _thread ,无论是2.7还是3.5都应该尽量避免使用较为底层的 thread/_thread 而应该使用 threading 。

创建一个线程可以通过实例化一个 threading.Thread 对象:

from threading import Thread import time def _sum(x, y): print("Compute {} + {}...".format(x, y)) time.sleep(2.0) return x+y def compute_sum(x, y): result = _sum(x, y) print("{} + {} = {}".format(x, y, result)) start = time.time() threads = [ Thread(target=compute_sum, args=(0,0)), Thread(target=compute_sum, args=(1,1)), Thread(target=compute_sum, args=(2,2)), ] for t in threads: t.start() for t in threads: t.join() print("Total elapsed time {} s".format(time.time() - start)) # Do not use Thread start = time.time() compute_sum(0,0) compute_sum(1,1) compute_sum(2,2) print("Total elapsed time {} s".format(time.time() - start)) Compute 0 + 0... Compute 1 + 1... Compute 2 + 2... 0 + 0 = 0 1 + 1 = 2 2 + 2 = 4 Total elapsed time 2.002729892730713 s Compute 0 + 0... 0 + 0 = 0 Compute 1 + 1... 1 + 1 = 2 Compute 2 + 2... 2 + 2 = 4 Total elapsed time 6.004806041717529 s 除了通过将函数传递给 Thread 创建线程实例之外,还可以直接继承 Thread 类:

from threading import Thread import time class ComputeSum(Thread): def __init__(self, x, y): super().__init__() self.x = x self.y = y def run(self): result = self._sum(self.x, self.y) print("{} + {} = {}".format(self.x, self.y, result)) def _sum(self, x, y): print("Compute {} + {}...".format(x, y)) time.sleep(2.0) return x+y threads = [ComputeSum(0,0), ComputeSum(1,1), ComputeSum(2,2)] start = time.time() for t in threads: t.start() for t in threads: t.join() print("Total elapsed time {} s".format(time.time() - start)) Compute 0 + 0... Compute 1 + 1... Compute 2 + 2... 0 + 0 = 0 1 + 1 = 2 2 + 2 = 4 Total elapsed time 2.001662015914917 s 根据上面代码执行的结果可以发现, compute_sum/t.run 函数的执行是按照 start() 的顺序,但 _sum 结果的输出顺序却是随机的。因为 _sum 中加入了 time.sleep(2.0) ,让程序执行到这里就会进入阻塞状态,但是几个线程的执行看起来却像是同时进行的(并发)。

有时候我们既需要并发地“跳过“阻塞的部分,又需要有序地执行其它部分,例如操作共享数据的时候,这时就需要用到”锁“。在上述”求和线程“的例子中,假设每次求和都需要加上额外的 _base 并把计算结果累积到 _base 中。尽管这个例子不太恰当,但它说明了线程锁的用途:

from threading import Thread, Lock import time _base = 1 _lock = Lock() class ComputeSum(Thread): def __init__(self, x, y): super().__init__() self.x = x self.y = y def run(self): result = self._sum(self.x, self.y) print("{} + {} + base = {}".format(self.x, self.y, result)) def _sum(self, x, y): print("Compute {} + {}...".format(x, y)) time.sleep(2.0) global _base with _lock: result = x + y + _base _base = result return result threads = [ComputeSum(0,0), ComputeSum(1,1), ComputeSum(2,2)] start = time.time() for t in threads: t.start() for t in threads: t.join() print("Total elapsed time {} s".format(time.time() - start)) Compute 0 + 0... Compute 1 + 1... Compute 2 + 2... 0 + 0 + base = 1 1 + 1 + base = 3 2 + 2 + base = 7 Total elapsed time 2.0064051151275635 s 这里用 上下文管理器 来管理锁的获取和释放,相当于:

_lock.acquire() try: result = x + y + _base _base = result finally: _lock.release() 死锁

线程的一大问题就是通过加锁来”抢夺“共享资源的时候有可能造成死锁,例如下面的程序:

from threading import Lock _base_lock = Lock() _pos_lock = Lock() _base = 1 def _sum(x, y): # Time 1 with _base_lock: # Time 3 with _pos_lock: result = x + y return result def _minus(x, y): # Time 0 with _pos_lock: # Time 2 with _base_lock: result = x - y return result 由于线程的调度执行顺序是不确定的,在执行上面两个线程 _sum/_minus 的时候就有可能出现注释中所标注的时间顺序,即 # Time 0 的时候运行到 with _pos_lock 获取了 _pos_lock 锁,而接下来由于阻塞马上切换到了 _sum 中的 # Time 1 ,并获取了 _base_lock ,接下来由于两个线程互相锁定了彼此需要的下一个锁,将会导致死锁,即程序无法继续运行。根据 我是一个线程 中所描述的,为了避免死锁,需要所有的线程按照指定的算法(或优先级)来进行加锁操作。不管怎么说,死锁问题都是一件非常伤脑筋的事,原因之一在于不管线程实现的是并发还是并行,在编程模型和语法上看起来都是并行的,而我们的大脑虽然是一个(内隐的)绝对并行加工的机器,却非常不善于将并行过程具象化(至少在未经足够训练的时候)。而与线程相比,协程(尤其是结合事件循环)无论在编程模型还是语法上,看起来都是非常友好的单线程同步过程。后面第二部分我们再来讨论 Python 中协程是如何从”小三“一步步扶正上位的 :D 。

协程

我之前翻译了Python 3.5 协程原理这篇文章之后尝试用了 Tornado + Motor 模式下的协程进行异步开发,确实感受到协程所带来的好处(至少是语法上的 :D )。至于协程的 async/await 语法是如何由开始的 yield 生成器一步一步上位至 Python 的 async/await 组合语句,前面那篇翻译的文章里面讲得已经非常详尽了。我们知道协程的本质上是:

allowing multiple entry points for suspending and resuming execution at certain locations.

允许多个入口对程序进行挂起、继续执行等操作,我们首先想到的自然也是生成器:

def jump_range(upper): index = 0 while index < upper: jump = yield index if jump is None: jump = 1 index += jump jump = jump_range(5) print(jump) print(jump.send(None)) print(jump.send(3)) print(jump.send(None)) <generator object jump_range at 0x10e283518> 0 3 4 后来又新增了 yield from 语法,可以将生成器串联起来:

def wait_index(i): # processing i... return (yield i) def jump_range(upper): index = 0 while index < upper: jump = yield from wait_index(index) if jump is None: jump = 1 index += jump jump = jump_range(5) print(jump) print(jump.send(None)) print(jump.send(3)) print(jump.send(None)) <generator object jump_range at 0x10e22a780> 0 3 4 yield from / send 似乎已经满足了协程所定义的需求,最初也确实是用 @types.coroutine 修饰器 将生成器转换成协程来使用,在 Python 3.5 之后则以专用的 async/await 取代了 @types.coroutine/yield from :

class Wait(object): """ 由于 Coroutine 协议规定 await 后只能跟 awaitable 对象, 而 awaitable 对象必须是实现了 __await__ 方法且返回迭代器 或者也是一个协程对象, 因此这里临时实现一个 awaitable 对象。 """ def __init__(self, index): self.index = index def __await__(self): return (yield self.index) async def jump_range(upper): index = 0 while index < upper: jump = await Wait(index) if jump is None: jump = 1 index += jump jump = jump_range(5) print(jump) print(jump.send(None)) print(jump.send(3)) print(jump.send(None)) <coroutine object jump_range at 0x10e2837d8> 0 3 4 与线程相比

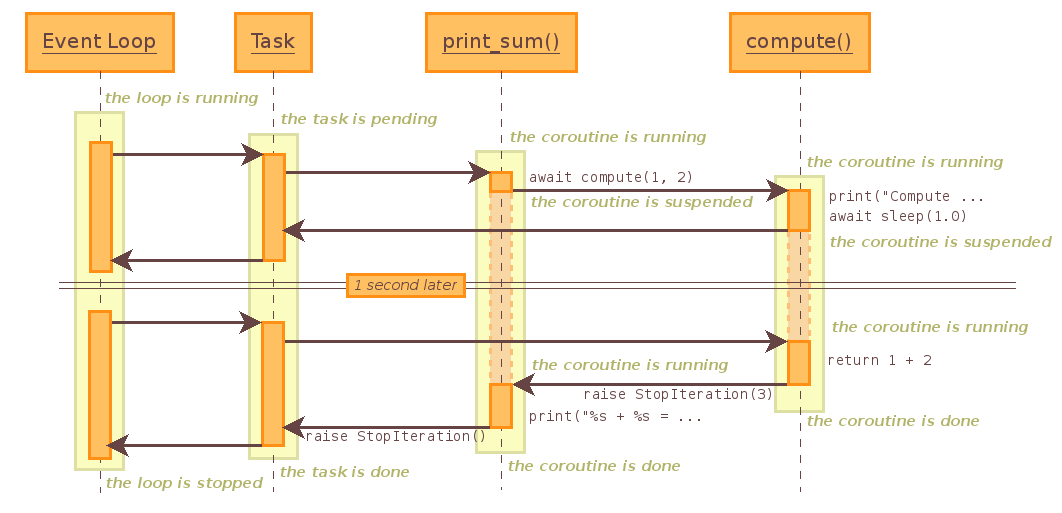

协程的执行过程如下所示:

import asyncio import time import types @types.coroutine def _sum(x, y): print("Compute {} + {}...".format(x, y)) yield time.sleep(2.0) return x+y @types.coroutine def compute_sum(x, y): result = yield from _sum(x, y) print("{} + {} = {}".format(x, y, result)) loop = asyncio.get_event_loop() loop.run_until_complete(compute_sum(0,0)) Compute 0 + 0... 0 + 0 = 0

这张图(来自: PyDocs: 18.5.3. Tasks and coroutines )清楚地描绘了由事件循环调度的协程的执行过程,上面的例子中事件循环的队列里只有一个协程,如果要与上一部分中线程实现的并发的例子相比较,只要向事件循环的任务队列中添加协程即可:

import asyncio import time # 上面的例子为了从生成器过度,下面全部改用 async/await 语法 async def _sum(x, y): print("Compute {} + {}...".format(x, y)) await asyncio.sleep(2.0) return x+y async def compute_sum(x, y): result = await _sum(x, y) print("{} + {} = {}".format(x, y, result)) start = time.time() loop = asyncio.get_event_loop() tasks = [ asyncio.ensure_future(compute_sum(0, 0)), asyncio.ensure_future(compute_sum(1, 1)), asyncio.ensure_future(compute_sum(2, 2)), ] loop.run_until_complete(asyncio.wait(tasks)) loop.close() print("Total elapsed time {}".format(time.time() - start)) Compute 0 + 0... Compute 1 + 1... Compute 2 + 2... 0 + 0 = 0 1 + 1 = 2 2 + 2 = 4 Total elapsed time 2.0042951107025146 总结

这两篇主要关于 Python 中的线程与协程的一些基本原理与用法,为此我搜索了不少参考文章与链接,对我自己理解它们的原理与应用场景也有很大的帮助(当然也有可能存在理解不到位的地方,欢迎指正)。当然在这里还是主要关注基于 Python 的语法与应用,如果想要了解更多底层实现的细节,可能需要从系统调度等底层技术细节开始学习(几年前我记得翻阅过《深入理解LINUX内核》这本书,虽然大部分细节已经记不清楚了,但对于理解其它人的分析、总结还是有一定帮助的)。这里讨论的基于协程的异步主要是借助于事件循环(由 asyncio 标准库提供),包括上文中的示意图,看起来很容易让人联想到 Node.js 的事件循环 & 回调,但是协程与回调也还是有区别的,具体就不在这里展开了,可以参考下面第一条参考链接。

参考

- Python 中的进程、线程、协程、同步、异步、回调

- 我是一个线程

- Concurrency is not Parallelism

- A Curious Course on Coroutines and Concurrency

- PyDocs: 17.1. threading — Thread-based parallelism

- PyDocs: 18.5.3. Tasks and coroutines

- [译] Python 3.5 协程究竟是个啥

- 协程的好处是什么? - crazybie 的回答

- Py3-cookbook:第十二章:并发编程

- Quora: What are the differences between parallel, concurrent and asynchronous programming?

- Real-time apps with gevent-socketio

![[HBLOG]公众号](https://www.liuhaihua.cn/img/qrcode_gzh.jpg)