使用Python和Pandas分析Pronto CycleShare数据

这是一篇非常不错的pandas 分析入门文章,在此简单翻译摘录如下。

本周,西雅图的自行车共享系统 Pronto CycleShare 一周岁了。 为了庆祝这一点,Pronto 提供了从第一年的数据缓存,并宣布了 Pronto Cycle Share 的数据分析挑战 。

你可以用很多工具分析这些数据,但我的选择工具是 Python。 在这篇文章中,我想展示如何开始分析这些数据,并使用 PyData 技术栈,即 NumPy , Pandas , Matplotlib 和 Seaborn 与其他可用的数据源。

这篇文章以 Jupyter Notebook 形式组织,它是一种开放的文档格式。结合了文本、代码、数据和图形,并且通过 Web 浏览器查看。本文中的内容可以下载对应的 Notebook 文件,并通过 Jupyter 打开。

下载 Pronto 的数据

我们可以从 Pronto 官网 下载对应的 数据文件 。总下载大约70MB,解压缩的文件大约900MB。

接下来我们需要导入一些 Python 包:

In [2]:

%matplotlib inline import matplotlib.pyplot as plt import pandas as pd import numpy as np import seaborn as sns; sns.set()

现在我们使用Pandas加载所有的行程记录:

In [3]:

trips = pd.read_csv('2015_trip_data.csv',

parse_dates=['starttime', 'stoptime'],

infer_datetime_format=True)

trips.head()

Out[3]:

| trip id | starttime | stoptime | bikeid | tripduration | fromstation name | tostation name | fromstation id | tostation_id | usertype | gender | birthyear | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 431 | 2014-10-13 10:31:00 | 2014-10-13 10:48:00 | SEA00298 | 985.935 | 2nd Ave & Spring St | Occidental Park / Occidental Ave S & S Washing... | CBD-06 | PS-04 | Annual Member | Male | 1960 |

| 1 | 432 | 2014-10-13 10:32:00 | 2014-10-13 10:48:00 | SEA00195 | 926.375 | 2nd Ave & Spring St | Occidental Park / Occidental Ave S & S Washing... | CBD-06 | PS-04 | Annual Member | Male | 1970 |

| 2 | 433 | 2014-10-13 10:33:00 | 2014-10-13 10:48:00 | SEA00486 | 883.831 | 2nd Ave & Spring St | Occidental Park / Occidental Ave S & S Washing... | CBD-06 | PS-04 | Annual Member | Female | 1988 |

| 3 | 434 | 2014-10-13 10:34:00 | 2014-10-13 10:48:00 | SEA00333 | 865.937 | 2nd Ave & Spring St | Occidental Park / Occidental Ave S & S Washing... | CBD-06 | PS-04 | Annual Member | Female | 1977 |

| 4 | 435 | 2014-10-13 10:34:00 | 2014-10-13 10:49:00 | SEA00202 | 923.923 | 2nd Ave & Spring St | Occidental Park / Occidental Ave S & S Washing... | CBD-06 | PS-04 | Annual Member | Male | 1971 |

这个行程数据集的每一行是由一个人单独骑行,共包含超过140,000条数据。

探索时间与行程的关系

让我们先看看一年中每日行程次数的趋势。

In [4]:

# Find the start date

ind = pd.DatetimeIndex(trips.starttime)

trips['date'] = ind.date.astype('datetime64')

trips['hour'] = ind.hour

In [5]:

# Count trips by date

by_date = trips.pivot_table('trip_id', aggfunc='count',

index='date',

columns='usertype', )

In [6]:

fig, ax = plt.subplots(2, figsize=(16, 8)) fig.subplots_adjust(hspace=0.4) by_date.iloc[:, 0].plot(ax=ax[0], title='Annual Members'); by_date.iloc[:, 1].plot(ax=ax[1], title='Day-Pass Users');

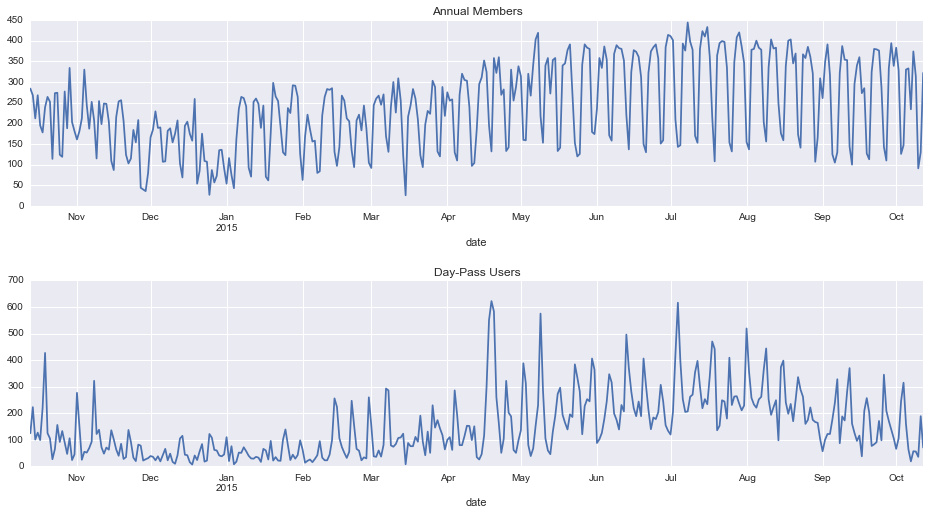

此图显示每日趋势,以年费用户(上图)和临时用户(下图)分隔。 根据图标,我们可以获得几个结论:

- 4月份短期使用的临时用户大幅增加可能是由于 美国规划协会全国会议 在西雅图市中心举行。 其他一个比较接近的时间是7月4日周末。

- 临时用户呈现了一个与季节相关联的稳定的衰退趋势; 年费用户的使用没有随着秋天的来临而显着减少。

- 年费用户和临时用户似乎都显示出明显的每周趋势。

现在放大每周趋势,看一下所有的骑乘都是按照星期几分部的。由于2015年1月份左右模式的变化,我们按照年份和星期几进行拆分:

In [7]:

by_weekday = by_date.groupby([by_date.index.year,

by_date.index.dayofweek]).mean()

by_weekday.columns.name = None # remove label for plot

fig, ax = plt.subplots(1, 2, figsize=(16, 6), sharey=True)

by_weekday.loc[2014].plot(title='Average Use by Day of Week (2014)', ax=ax[0]);

by_weekday.loc[2015].plot(title='Average Use by Day of Week (2015)', ax=ax[1]);

for axi in ax:

axi.set_xticklabels(['Mon', 'Tues', 'Wed', 'Thurs', 'Fri', 'Sat', 'Sun'])

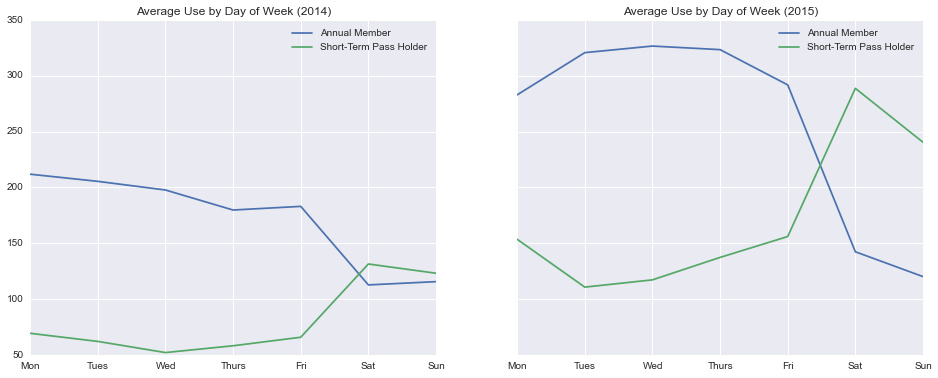

我们看到了一个互补的模式:年费用户倾向于工作日使用他们的自行车(即作为通勤的一部分),而临时用户倾向于在周末使用他们的自行车。这种模式甚至在2015年年初都没有特别的体现出来,尤其是年费用户:似乎在头几个月,用户还没有使用 Pronto 的通勤习惯。

查看平日和周末的平均每小时骑行也很有趣。这需要一些操作:

In [8]:

# count trips by date and by hour

by_hour = trips.pivot_table('trip_id', aggfunc='count',

index=['date', 'hour'],

columns='usertype').fillna(0).reset_index('hour')

# average these counts by weekend

by_hour['weekend'] = (by_hour.index.dayofweek >= 5)

by_hour = by_hour.groupby(['weekend', 'hour']).mean()

by_hour.index.set_levels([['weekday', 'weekend'],

["{0}:00".format(i) for i in range(24)]],

inplace=True);

by_hour.columns.name = None

现在我们可以绘制结果来查看每小时的趋势:

In [9]:

fig, ax = plt.subplots(1, 2, figsize=(16, 6), sharey=True)

by_hour.loc['weekday'].plot(title='Average Hourly Use (Mon-Fri)', ax=ax[0])

by_hour.loc['weekend'].plot(title='Average Hourly Use (Sat-Sun)', ax=ax[1])

ax[0].set_ylabel('Average Trips per Hour');

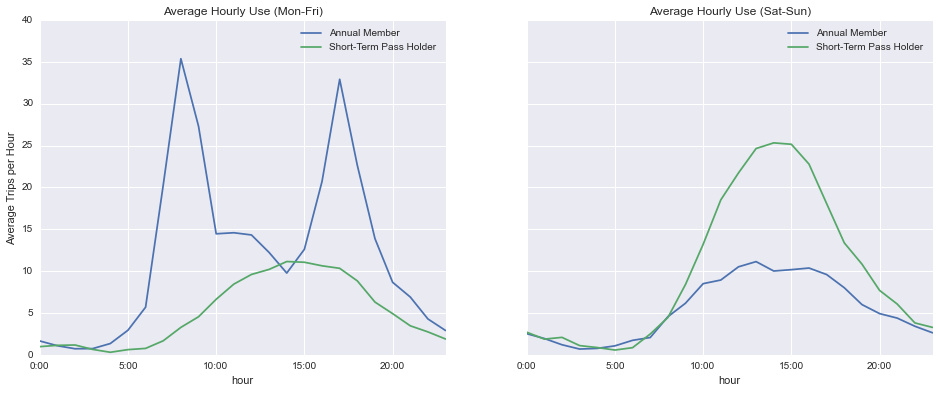

我们看到一个“通勤”模式和一个“娱乐”模式之间的明显区别:“通勤”模式在早上和晚上急剧上升,而“娱乐”模式在下午的时候有一个宽峰。 有趣的是,年费会员在周末的行为似乎与临时用户在周末的行为几乎相同。

旅行时间

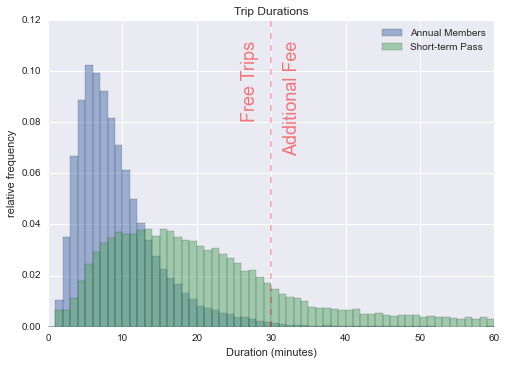

接下来,我们来看看旅行的持续时间。 Pronto 免费骑行最长可达30分钟; 任何长于此的单次使用,在前半个小时都会产生几美元的使用费,此后每小时大约需要十美元。

让我们看看年费会员和临时使用者的旅行持续时间的分布:

In [10]:

trips['minutes'] = trips.tripduration / 60

trips.groupby('usertype')['minutes'].hist(bins=np.arange(61), alpha=0.5, normed=True);

plt.xlabel('Duration (minutes)')

plt.ylabel('relative frequency')

plt.title('Trip Durations')

plt.text(34, 0.09, "Free Trips/n/nAdditional Fee", ha='right',

size=18, rotation=90, alpha=0.5, color='red')

plt.legend(['Annual Members', 'Short-term Pass'])

plt.axvline(30, linestyle='--', color='red', alpha=0.3);

在这里,我添加了一个红色的虚线,分开免费骑乘(左)和付费骑乘(右)。看来,年费用户对系统规则更加了解:只有行程分布的一小部分超过30分钟。另一方面,大约四分之一的临时用户时间超过半小时限制,并收取额外费用。 我的预期是,这些临时用户不能很好理解这种定价结构,并且可能会因为不开心的体验不再使用。

估计行程距离

看看旅行的距离也十分有趣。Pronto 发布的数据中不包括行车的距离,因此我们需要通过其他来源来确定。让我们从加载行车数据开始 - 因为一些行程在Pronto的服务点之间开始和结束,我们将其添加为一个“车站”:

In [11]:

stations = pd.read_csv('2015_station_data.csv')

pronto_shop = dict(id=54, name="Pronto shop",

terminal="Pronto shop",

lat=47.6173156, long=-122.3414776,

dockcount=100, online='10/13/2014')

stations = stations.append(pronto_shop, ignore_index=True)

现在我们需要找到两对纬度/经度坐标之间的骑车距离。幸运的是,Google 地图有一个距离 API,我们可以免费使用。

从文档中知道,我们每天免费使用的限制为每天最多 2500 个距离,每 10 秒最多 100 个距离。现在有 55 个站,我们有(55 * 54/2) = 1485 个非零距离,所以我们可以在几天内免费查询所有车站之间的距离。

为此,我们一次查询一行,在查询之间等待10+秒(注意:我们可能还会使用 googlemaps Python 包 ,但使用它需要获取 API 密钥)。

In [12]:

from time import sleep

def query_distances(stations=stations):

"""Query the Google API for bicycling distances"""

latlon_list = ['{0},{1}'.format(lat, long)

for (lat, long) in zip(stations.lat, stations.long)]

def create_url(i):

URL = ('https://maps.googleapis.com/maps/api/distancematrix/json?'

'origins={origins}&destinations={destinations}&mode=bicycling')

return URL.format(origins=latlon_list[i],

destinations='|'.join(latlon_list[i + 1:]))

for i in range(len(latlon_list) - 1):

url = create_url(i)

filename = "distances_{0}.json".format(stations.terminal.iloc[i])

print(i, filename)

!curl "{url}" -o {filename}

sleep(11) # only one query per 10 seconds!

def build_distance_matrix(stations=stations):

"""Build a matrix from the Google API results"""

dist = np.zeros((len(stations), len(stations)), dtype=float)

for i, term in enumerate(stations.terminal[:-1]):

filename = 'queried_distances/distances_{0}.json'.format(term)

row = json.load(open(filename))

dist[i, i + 1:] = [el['distance']['value'] for el in row['rows'][0]['elements']]

dist += dist.T

distances = pd.DataFrame(dist, index=stations.terminal,

columns=stations.terminal)

distances.to_csv('station_distances.csv')

return distances

# only call this the first time

import os

if not os.path.exists('station_distances.csv'):

# Note: you can call this function at most ~twice per day!

query_distances()

# Move all the queried files into a directory

# so we don't accidentally overwrite them

if not os.path.exists('queried_distances'):

os.makedirs('queried_distances')

!mv distances_*.json queried_distances

# Build distance matrix and save to CSV

distances = build_distance_matrix()

这里是第一个5x5距离矩阵:

In [13]:

distances = pd.read_csv('station_distances.csv', index_col='terminal')

distances.iloc[:5, :5]

Out[13]:

| BT-01 | BT-03 | BT-04 | BT-05 | CBD-13 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| terminal | |||||

| BT-01 | 0 | 422 | 1067 | 867 | 1342 |

| BT-03 | 422 | 0 | 838 | 445 | 920 |

| BT-04 | 1067 | 838 | 0 | 1094 | 1121 |

| BT-05 | 867 | 445 | 1094 | 0 | 475 |

| CBD-13 | 1342 | 920 | 1121 | 475 | 0 |

让我们将这些距离转换为英里,并将它们加入我们的行程数据:

In [14]:

stacked = distances.stack() / 1609.34 # convert meters to miles stacked.name = 'distance' trips = trips.join(stacked, on=['from_station_id', 'to_station_id'])

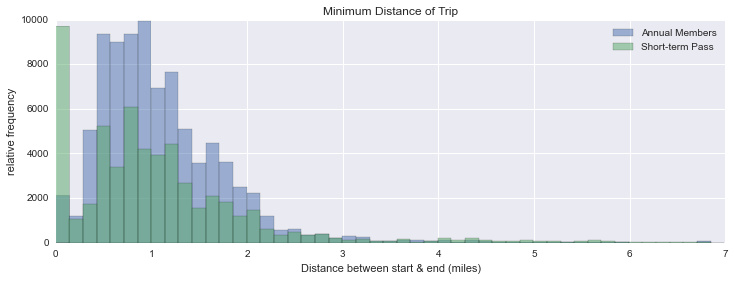

现在我们可以绘制行程距离的分布:

In [15]:

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(12, 4))

trips.groupby('usertype')['distance'].hist(bins=np.linspace(0, 6.99, 50),

alpha=0.5, ax=ax);

plt.xlabel('Distance between start & end (miles)')

plt.ylabel('relative frequency')

plt.title('Minimum Distance of Trip')

plt.legend(['Annual Members', 'Short-term Pass']);

请记住,这显示站点之间的最短可能距离,是每次行程上实际距离的下限。许多旅行(特别是临时用户)在几个街区内开始和结束。除此之外,旅行高峰一般在大约1英里左右,也有一些用户将他们的旅行距离扩展到四英里或更长的距离。

骑手速度

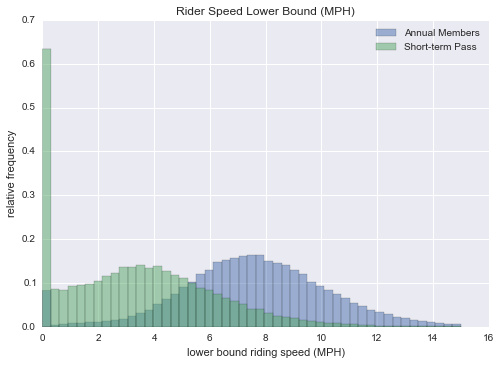

给定这些距离,我们还可以计算估计骑行速度的下限。 让我们这样做,然后看看年费用户和临时用户的速度分布:

In [16]:

trips['speed'] = trips.distance * 60 / trips.minutes

trips.groupby('usertype')['speed'].hist(bins=np.linspace(0, 15, 50), alpha=0.5, normed=True);

plt.xlabel('lower bound riding speed (MPH)')

plt.ylabel('relative frequency')

plt.title('Rider Speed Lower Bound (MPH)')

plt.legend(['Annual Members', 'Short-term Pass']);

有趣的是,分布是完全不同的,年费用户的速度平均值更高一些。你可能会想到这里的结论,年费用户的速度比临时用户更高,但数据本身不足以支持这一结论。如果年费用户倾向于通过最直接的路线从点A去往点B,那么这些数据也可以被解释,而临时用户倾向于绕行并间接到达他们的目的地。我怀疑现实是这两种效应的混合。

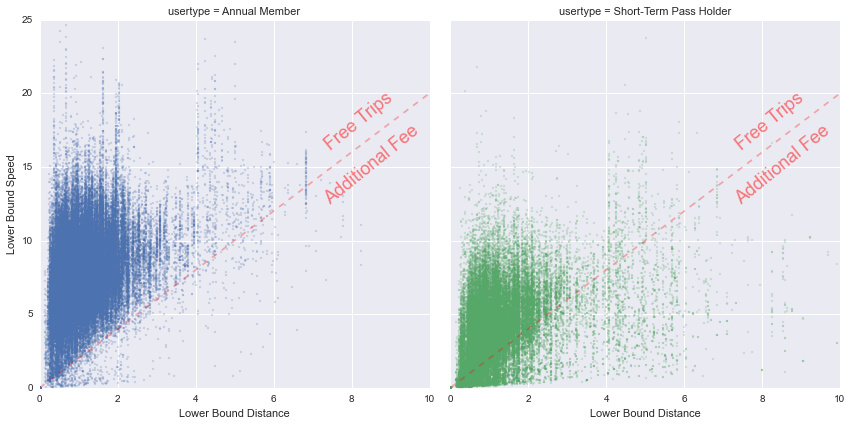

还要看看距离和速度之间的关系:

In [17]:

g = sns.FacetGrid(trips, col="usertype", hue='usertype', size=6)

g.map(plt.scatter, "distance", "speed", s=4, alpha=0.2)

# Add lines and labels

x = np.linspace(0, 10)

g.axes[0, 0].set_ylabel('Lower Bound Speed')

for ax in g.axes.flat:

ax.set_xlabel('Lower Bound Distance')

ax.plot(x, 2 * x, '--r', alpha=0.3)

ax.text(9.8, 16.5, "Free Trips/n/nAdditional Fee", ha='right',

size=18, rotation=39, alpha=0.5, color='red')

ax.axis([0, 10, 0, 25])

总的来说,我们看到较长的路途速度更快 - 虽然这受到与上述相同的下限影响。如上所述,作为参考,我绘制了需要的红线用于区分额外费用(低于红线)和免费费用(红线以上)。我们再次看到,年度会员对于不超过半小时的限制比每天通过用户更加精明 - 点的分布的指向了用户注意了他们使用的时间,以避免额外的费用。

海拔高度

在西雅图自行车分享服务的可行性的一个焦点是,西雅图是一个丘陵城市。在服务发布之前,一些分析师预测,西雅图会有源源不断的自行车上坡下坡,所以并不适合分享单车系统的落地。

数据版本中不包含海拔高度数据,但我们可以转到 Google Maps API 获取我们需要的数据; 请参阅 此网站 了解海拔 API 的描述。

在这种情况下,自由使用限制为每天 2500 个请求,每次请求最多包含 512 个海拔高度。 由于我们只需要55个海拔高度,我们可以在单个查询中执行:

In [18]:

def get_station_elevations(stations):

"""Get station elevations via Google Maps API"""

URL = "https://maps.googleapis.com/maps/api/elevation/json?locations="

locs = '|'.join(['{0},{1}'.format(lat, long)

for (lat, long) in zip(stations.lat, stations.long)])

URL += locs

!curl "{URL}" -o elevations.json

def process_station_elevations():

"""Convert Elevations JSON output to CSV"""

import json

D = json.load(open('elevations.json'))

def unnest(D):

loc = D.pop('location')

loc.update(D)

return loc

elevs = pd.DataFrame([unnest(item) for item in D['results']])

elevs.to_csv('station_elevations.csv')

return elevs

# only run this the first time:

import os

if not os.path.exists('station_elevations.csv'):

get_station_elevations(stations)

process_station_elevations()

现在让我们读入海拔高度数据:

In [19]:

elevs = pd.read_csv('station_elevations.csv', index_col=0)

elevs.head()

Out[19]:

| elevation | lat | lng | resolution | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 37.351780 | 47.618418 | -122.350964 | 76.351616 |

| 1 | 33.815830 | 47.615829 | -122.348564 | 76.351616 |

| 2 | 34.274055 | 47.616094 | -122.341102 | 76.351616 |

| 3 | 44.283257 | 47.613110 | -122.344208 | 76.351616 |

| 4 | 42.460381 | 47.610185 | -122.339641 | 76.351616 |

为了验证结果,我们需要仔细检查纬度和经度是否匹配:

In [20]:

# double check that locations match print(np.allclose(stations.long, elevs.lng)) print(np.allclose(stations.lat, elevs.lat))

True True

现在我们可以将海拔数据与行程数据整合:

In [21]:

stations['elevation'] = elevs['elevation'] elevs.index = stations['terminal'] trips['elevation_start'] = trips.join(elevs, on='from_station_id')['elevation'] trips['elevation_end'] = trips.join(elevs, on='to_station_id')['elevation'] trips['elevation_gain'] = trips['elevation_end'] - trips['elevation_start']

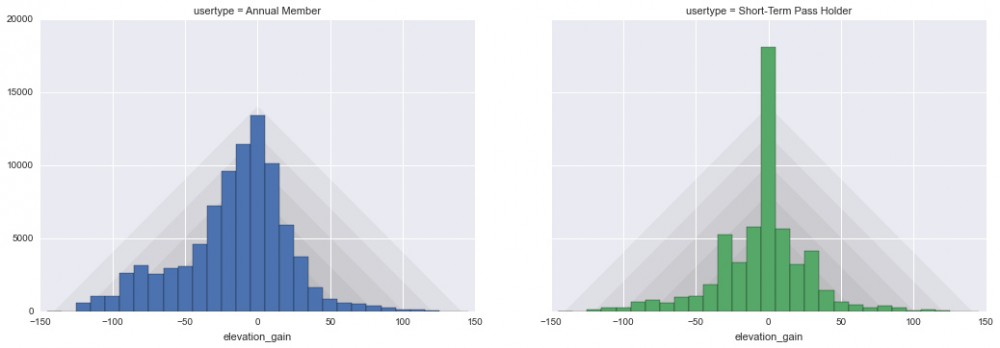

让我们来看看海拔数据和会员类型的分布关系:

In [22]:

g = sns.FacetGrid(trips, col="usertype", hue='usertype')

g.map(plt.hist, "elevation_gain", bins=np.arange(-145, 150, 10))

g.fig.set_figheight(6)

g.fig.set_figwidth(16);

# plot some lines to guide the eye

for lim in range(60, 150, 20):

x = np.linspace(-lim, lim, 3)

for ax in g.axes.flat:

ax.fill(x, 100 * (lim - abs(x)),

color='gray', alpha=0.1, zorder=0)

我们在背景中绘制了一些阴影以帮助引导分析。 年度会员和临时用户之间有很大的区别:年费用户非常明显的表示出偏好下坡行程(左侧的分布),而临时用户表现并不明显,而是表示喜欢骑乘开始并在相同高度结束。

为了使海拔数据变化的影响更加明显,我们做一些计算:

In [23]:

print("total downhill trips:", (trips.elevation_gain < 0).sum())

print("total uphill trips: ", (trips.elevation_gain > 0).sum())

total downhill trips: 80532 total uphill trips: 50493

我们看到,第一年下坡比上坡多出了 3 万次 - 这是大约 60% 以上。 根据目前的使用水平,这意味着 Pronto 工作人员必须每天从海拔较低的服务点运送大约 100 辆自行车到高海拔服务点。

天气

另一个常见的反对循环共享的可行性的论点是天气。让我们来看看出行数量随着温度和降水量的变化。

幸运的是,数据包括了大范围的天气数据:

In [24]:

weather = pd.read_csv('2015_weather_data.csv', index_col='Date', parse_dates=True)

weather.columns

Out[24]:

Index(['Max_Temperature_F', 'Mean_Temperature_F', 'Min_TemperatureF',

'Max_Dew_Point_F', 'MeanDew_Point_F', 'Min_Dewpoint_F', 'Max_Humidity',

'Mean_Humidity ', 'Min_Humidity ', 'Max_Sea_Level_Pressure_In ',

'Mean_Sea_Level_Pressure_In ', 'Min_Sea_Level_Pressure_In ',

'Max_Visibility_Miles ', 'Mean_Visibility_Miles ',

'Min_Visibility_Miles ', 'Max_Wind_Speed_MPH ', 'Mean_Wind_Speed_MPH ',

'Max_Gust_Speed_MPH', 'Precipitation_In ', 'Events'],

dtype='object')

dtype ='object')

让我们将天气数据与行程数据结合起来:

In [25]:

by_date = trips.groupby(['date', 'usertype'])['trip_id'].count()

by_date.name = 'count'

by_date = by_date.reset_index('usertype').join(weather)

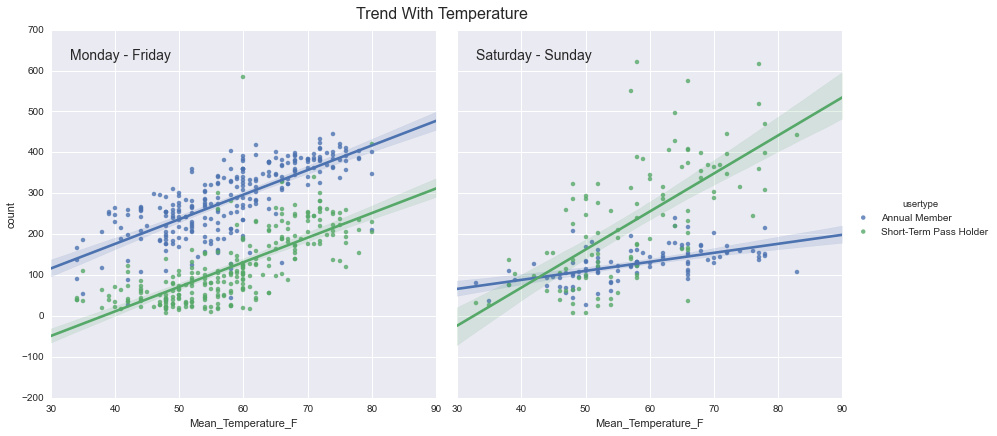

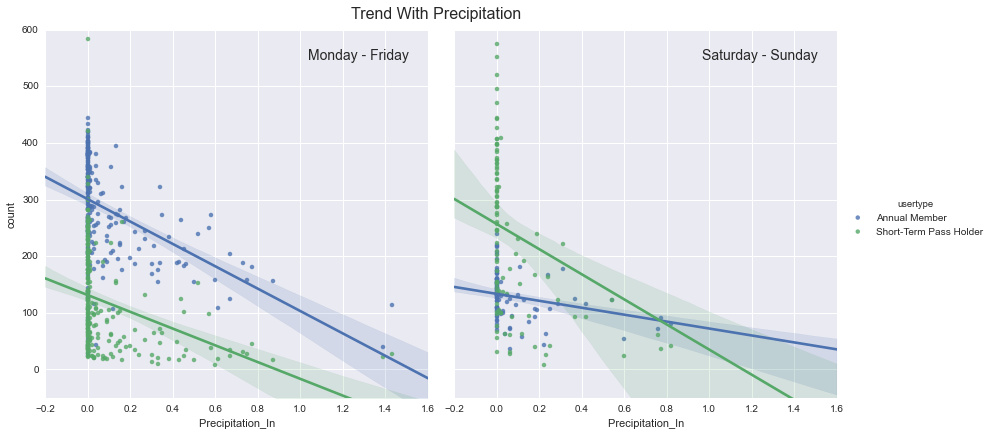

现在我们可以看看按工作日和周末为纬度,查看出行数量随温度和降水量的变化:

In [26]:

# add a flag indicating weekend

by_date['weekend'] = (by_date.index.dayofweek >= 5)

#----------------------------------------------------------------

# Plot Temperature Trend

g = sns.FacetGrid(by_date, col="weekend", hue='usertype', size=6)

g.map(sns.regplot, "Mean_Temperature_F", "count")

g.add_legend();

# do some formatting

g.axes[0, 0].set_title('')

g.axes[0, 1].set_title('')

g.axes[0, 0].text(0.05, 0.95, 'Monday - Friday', va='top', size=14,

transform=g.axes[0, 0].transAxes)

g.axes[0, 1].text(0.05, 0.95, 'Saturday - Sunday', va='top', size=14,

transform=g.axes[0, 1].transAxes)

g.fig.text(0.45, 1, "Trend With Temperature", ha='center', va='top', size=16);

#----------------------------------------------------------------

# Plot Precipitation

g = sns.FacetGrid(by_date, col="weekend", hue='usertype', size=6)

g.map(sns.regplot, "Precipitation_In ", "count")

g.add_legend();

# do some formatting

g.axes[0, 0].set_ylim(-50, 600);

g.axes[0, 0].set_title('')

g.axes[0, 1].set_title('')

g.axes[0, 0].text(0.95, 0.95, 'Monday - Friday', ha='right', va='top', size=14,

transform=g.axes[0, 0].transAxes)

g.axes[0, 1].text(0.95, 0.95, 'Saturday - Sunday', ha='right', va='top', size=14,

transform=g.axes[0, 1].transAxes)

g.fig.text(0.45, 1, "Trend With Precipitation", ha='center', va='top', size=16);

对于天气的影响,我们可以看出明显的趋势:人们更喜欢温暖、阳光明媚的天气。但是也有一些有趣的细节:工作日期间,所有的用户都受到天气的影响。然而周末年费用户受影响更少。我没有什么好的理论说明为什么有这种趋势,如果你有好的想法,欢迎提供。

总结

根据上面的一些系列分析,但是我想我们可以从这些数据中获得一些结论:

- 年费用户与临时用户整体上会有不同的行为:年费用户通常是利用 Pronto 进行工作日的通勤。临时用户则是周末使用 Pronto 探索城市的特定区域。

- 尽管年费用户对定价策略有所了解,但是四分之一的行程还是超过了半小时的限制,并产生了额外的费用。为了客户的权益,Pronto 应该更好告知用户这种定价策略。

- 海拔和天气会影响使用,正如你预计的一样:下坡比上坡多60%,寒冷和下雨也会明显减少当天的骑行数量。

![[HBLOG]公众号](https://www.liuhaihua.cn/img/qrcode_gzh.jpg)