从 Memory Reordering 说起

关注“光谷码农”微信公众好,学习最前沿最深度的Go语言技术。

下面这段代码会有怎样的输出

var x, y int

go func() {

x = 1 // A1

fmt.Print("y:", y, " ") // A2

}()

go func() {

y = 1 // B1

fmt.Print("x:", x, " ") // B2

}()

显而易见的几种结果:

y:0 x:1 x:0 y:1 x:1 y:1 y:1 x:1

令人意外的结果

x:0 y:0 y:0 x:0

这种令人意外的结果被称为内存重排: Memory Reordering

什么是内存重排

内存重排指的是内存的读/写指令重排。

— Xargin

软件或硬件系统可以根据其对代码的分析结果,一定程度上打乱代码的执行顺序,以达到其不可告人的目的。

为什么会发生内存重排

编译器重排

snippet 1

X = 0

for i in range(100):

X = 1

print X

snippet 2

X = 1

for i in range(100):

print X

snippet 1 和 snippet 2 是等价的。

如果这时候,假设有 Processor 2 同时在执行一条指令:

X = 0

P2 中的指令和 snippet 1 交错执行时,可能产生的结果是:111101111..

P2 中的指令和 snippet 2 交错执行时,可能产生的结果是:11100000…

在多核心场景下,没有办法轻易地判断两段程序是“等价”的。

CPU 重排

litmus 验证

cat sb.litmus

X86 SB

{ x=0; y=0; }

P0 | P1 ;

MOV [x],$1 | MOV [y],$1 ;

MOV EAX,[y] | MOV EAX,[x] ;

locations [x;y;]

exists (0:EAX=0 // 1:EAX=0)

⇒

~ ❯❯❯ bin/litmus7 ./sb.litmus

%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%

% Results for ./sb.litmus %

%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%

X86 SB

{x=0; y=0;}

P0 | P1 ;

MOV [x],$1 | MOV [y],$1 ;

MOV EAX,[y] | MOV EAX,[x] ;

locations [x; y;]

exists (0:EAX=0 // 1:EAX=0)

Generated assembler

##START _litmus_P0

movl $1, -4(%rbx,%rcx,4)

movl -4(%rsi,%rcx,4), %eax

##START _litmus_P1

movl $1, -4(%rsi,%rcx,4)

movl -4(%rbx,%rcx,4), %eax

Test SB Allowed

Histogram (4 states)

96 *>0:EAX=0; 1:EAX=0; x=1; y=1;

499878:>0:EAX=1; 1:EAX=0; x=1; y=1;

499862:>0:EAX=0; 1:EAX=1; x=1; y=1;

164 :>0:EAX=1; 1:EAX=1; x=1; y=1;

Ok

Witnesses

Positive: 96, Negative: 999904

Condition exists (0:EAX=0 // 1:EAX=0) is validated

Hash=2d53e83cd627ba17ab11c875525e078b

Observation SB Sometimes 96 999904

Time SB 0.11

CPU 架构

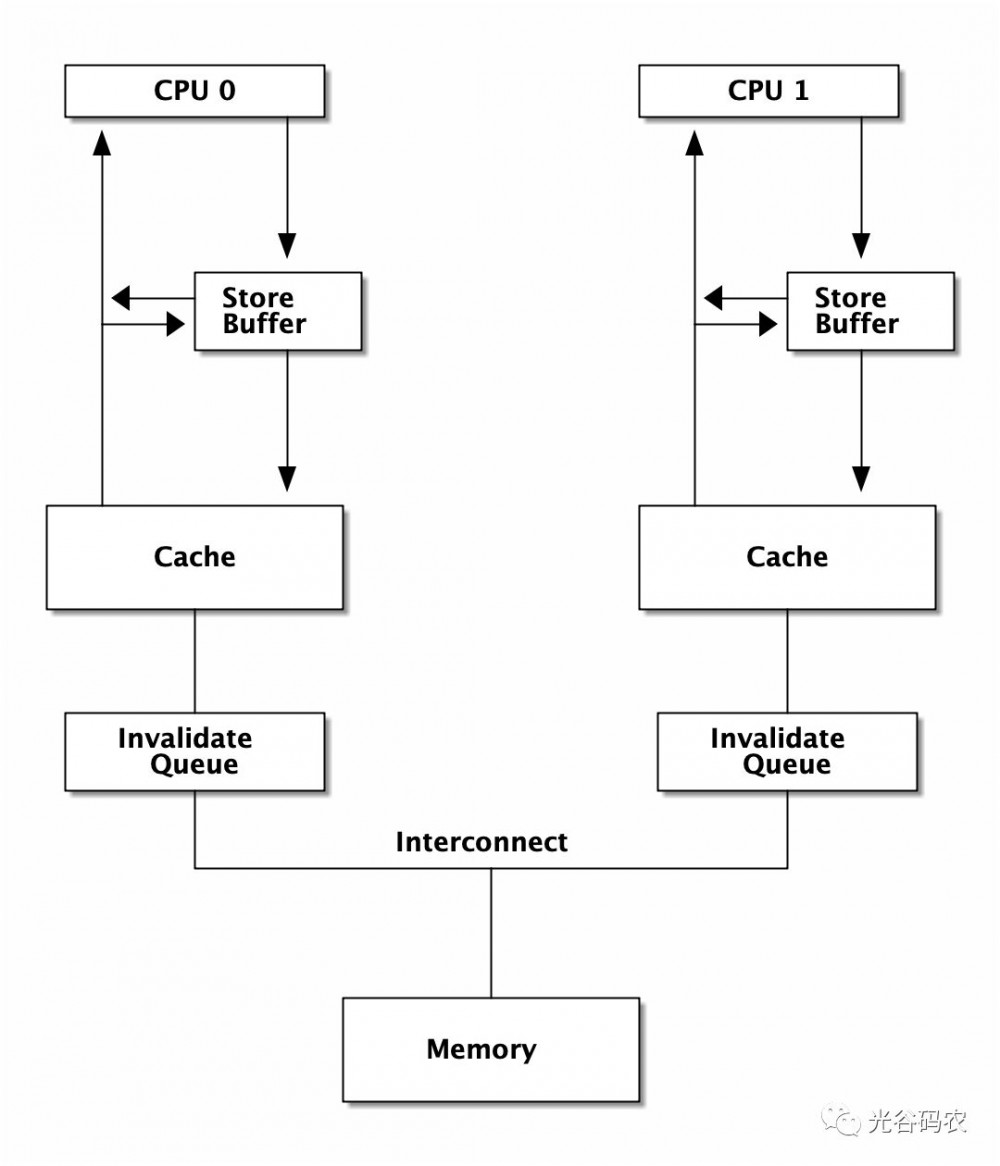

Figure 1. CPU Architecture

Figure 2. Store Buffer

这里的 Invalidate Queue 实际上稍微有一些简化,真实世界的 CPU 在做 invalidate 操作时还是挺麻烦的:

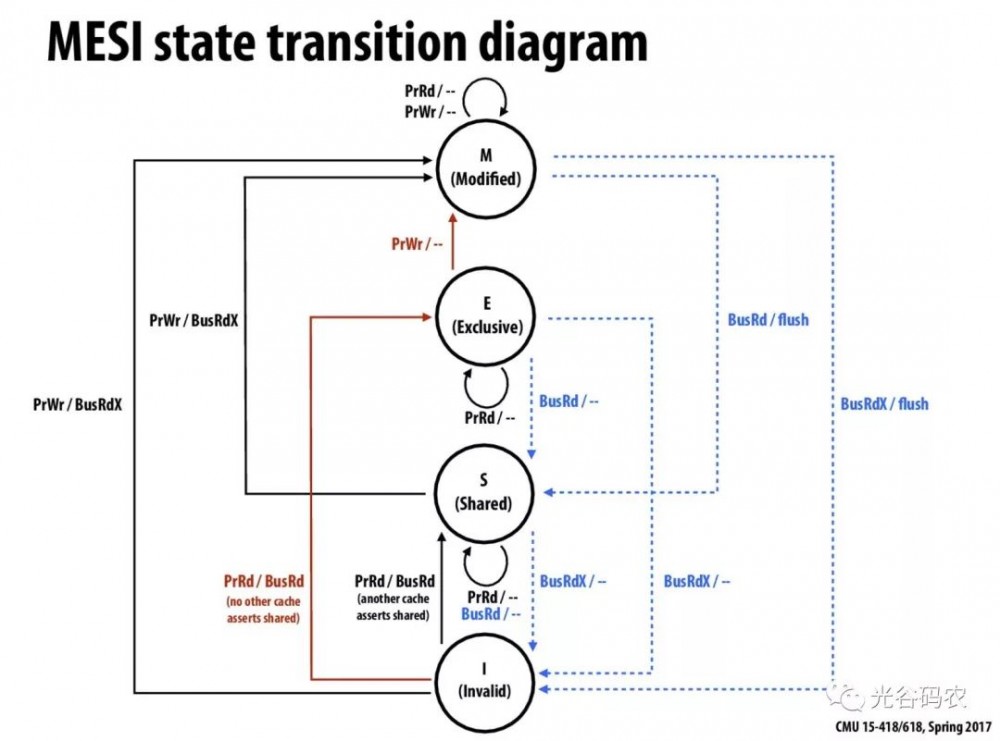

Figure 3. MESI Protocol

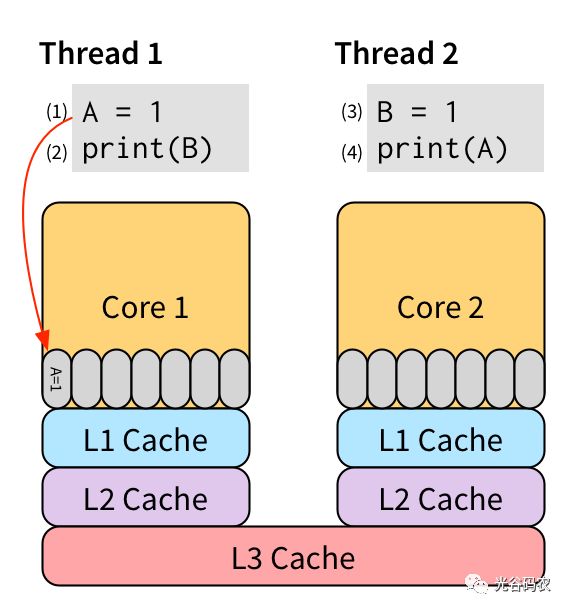

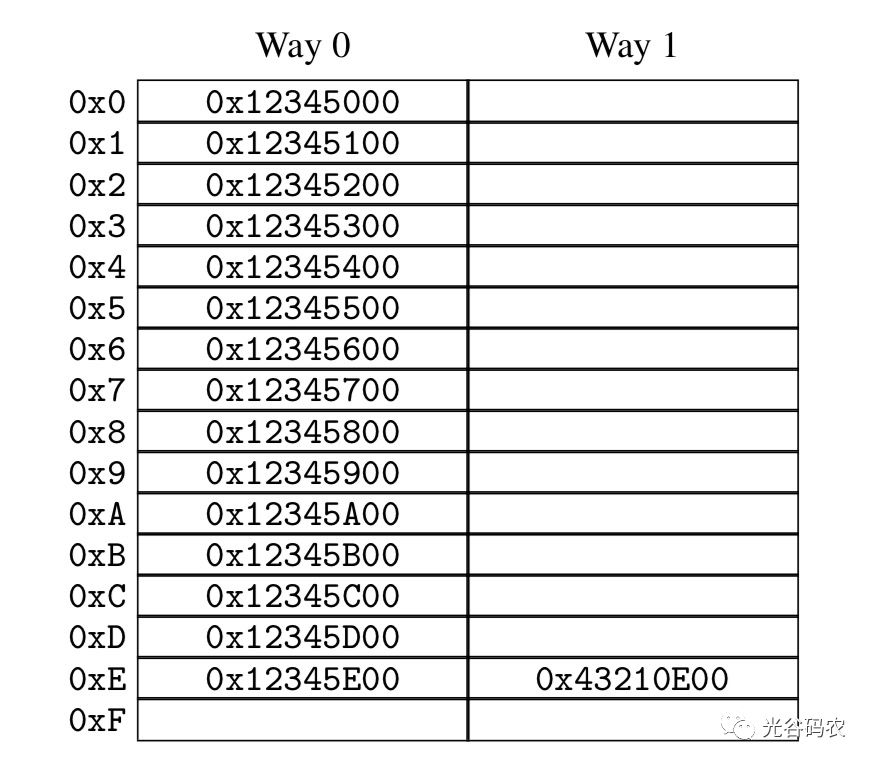

Figure 4. CPU Cache Structure

内存重排的目的

当然是为了优化啊。这还用说吗

-

减少程序指令数

-

最大化提高 CPU 利用率。

当我们需要顺序的时候,我们在讨论些什么

memory barrier

A memory barrier, also known as a membar, memory fence or fence instruction, is a type of barrier instruction that causes a central processing unit (CPU) or compiler to enforce an ordering constraint on memory operations issued before and after the barrier instruction.

— wikipedia

有了 memory barrier,才能实现应用层的各种同步原语。如 atomic,而 atomic 又是各种更上层 lock 的基础。

atomic

On x86, it will turn into a lock prefixed assembly instruction, like LOCK XADD. Being a single instruction, it is non-interruptible. As an added "feature", the lock prefix results in a full memory barrier

— Stackoverflow

"…locked operations serialize all outstanding load and store operations (that is, wait for them to complete)." …"Locked operations are atomic with respect to all other memory operations and all externally visible events. Only instruction fetch and page table accesses can pass locked instructions. Locked instructions can be used to synchronize data written by one processor and read by another processor." -

— Intel® 64 and IA-32 Architectures Software Developer’s Manual Chapter 8.1.2.

atomic 应用示例:双buffer

var doublebuffer struct {

buffer [2]option

idx int64

}

atomic.Load(&doublebuffer.idx)

atomic.CompareAndSwapInt64(&doublebuffer.idx, doublebuffer.idx, 1-doublebuffer.idx)

option 可以是任意的自定义数据结构。

lock

概念和用法就不讲了,你们应该都用过。没有免费的午餐,有锁冲突就会大幅度降低性能。

为了减小对性能的影响,锁应尽量减小粒度,并且不在互斥区内放入耗时操作,但是总是有一些悲伤的故事:

sync.Pool 中的锁

var (

allPoolsMu Mutex

allPools []*Pool

)

func (p *Pool) pinSlow() *poolLocal {

allPoolsMu.Lock()

defer allPoolsMu.Unlock()

pid := runtime_procPin()

if p.local == nil {

allPools = append(allPools, p)

}

//........

return &local[pid]

}

udp WriteTo 的锁

func (fd *FD) WriteTo(p []byte, sa syscall.Sockaddr) (int, error) {

if err := fd.writeLock(); err != nil {

return 0, err

}

defer fd.writeUnlock()

if err := fd.pd.prepareWrite(fd.isFile); err != nil {

return 0, err

}

for {

err := syscall.Sendto(fd.Sysfd, p, 0, sa)

if err == syscall.EAGAIN && fd.pd.pollable() {

if err = fd.pd.waitWrite(fd.isFile); err == nil {

continue

}

}

if err != nil {

return 0, err

}

return len(p), nil

}

}

tcp transport 上也有锁!

type Transport struct {

idleMu sync.Mutex

wantIdle bool // user has requested to close all idle conns

idleConn map[connectMethodKey][]*persistConn // most recently used at end

idleConnCh map[connectMethodKey]chan *persistConn

idleLRU connLRU

reqMu sync.Mutex

reqCanceler map[*Request]func(error)

altMu sync.Mutex // guards changing altProto only

altProto atomic.Value // of nil or map[string]RoundTripper, key is URI scheme

connCountMu sync.Mutex

connPerHostCount map[connectMethodKey]int

connPerHostAvailable map[connectMethodKey]chan struct{}

//......

会不会碰上瓶颈要随缘。

你的系统在锁上出问题的最明显特征

-

压测过不了几千级别的 QPS(丢人!

-

Goroutine 一开始很稳定,超过一定 QPS 之后暴涨

-

可以通过压测方便地发现问题。

lock contention 的本质问题是需要进入互斥区的 g 需要等待独占 g 退出后才能进入互斥区,并行 → 串行

cache contention

cache contention 那也是 contention,使用 atomic,或者 false sharing 就会导致 cache contention。

atomic 操作可以理解成 “true sharing”。

症状:在核心数增多时,单次操作的成本上升,导致程序整体性能下降。

true sharing

例子:

RWMutex 的 RLock:

func (rw *RWMutex) RLock() {

// ....

if atomic.AddInt32(&rw.readerCount, 1) < 0 {

// A writer is pending, wait for it.

runtime_SemacquireMutex(&rw.readerSem, false)

}

// else 获取 RLock 成功

// ....

}

true sharing 带来的问题:

sync: RWMutex scales poorly with CPU count

— issue 17973

至今还没有解决这个问题,如果解决了的话,根本不需要 sync.Map 出现了。

false sharing

runtime/sema.go

var semtable [semTabSize]struct {

root semaRoot

pad [cpu.CacheLinePadSize - unsafe.Sizeof(semaRoot{})]byte

}

runtime/time.go

var timers [timersLen]struct {

timersBucket

// The padding should eliminate false sharing

// between timersBucket values.

pad [cpu.CacheLinePadSize - unsafe.Sizeof(timersBucket{})%cpu.CacheLinePadSize]byte

}

本来每个核心(在 Go 里的 GPM 中的 P 概念)独享的数据,如果发生 false sharing 了会怎么样?

思考题:

二维数组求和,横着遍历和竖着遍历哪种更快,为什么?

为什么 Go 官方坚持不在 sync.Map 上增加 Len 方法?

欢迎关注“网易云课堂·光谷码农课堂”

![[HBLOG]公众号](https://www.liuhaihua.cn/img/qrcode_gzh.jpg)